As some of you will know, John Hall Thorpe training was in commercial work in Sydney where he was on the staff of two newspapers before he moved to Britain in He had already made a few etching whilst in Australia and did not exhibit any colour woodcuts until the end of the first war. But when he did, these prints were important in the revival of colour woodcut in the 1920s. As you may also know, Hall Thorpe never printed his own work and acknowledged the printing was done under his supervision. This meant he was unable to exhibit with the Graver Printers though he gained by having much larger editions to sell. If he went to a commercial printer (and I think be did) he was also limited by the numbers and subtlety of the colours he used. But if you look carefully at his prints, what stands out is how successful his economy of means was.

William Bemrose (or Bemrose and Sons as it became) certainly worked with Hall Thorpe on prints like Summer (top) which was published in 1929. Bemrose set up in Derby as a maker of railway timetables in 1826 and naturally worked with the Midland Railway whose main base was at Derby Station (destroyed by British Rail). The fine engraving below of the station was made by them in 1840 and you will be pleased to know the memorable clock tower to the left remains unmolested 180 years later. Features like the tower were typical of the Midland's serious attitude to public architecture. John Ruskin was appalled by their plans to drive the main line through from Matlock to Chinley but no one seeing the grandeur of the remote viaduct over the Derwent at Monsall Dale could fail to be impressed.

The firm did everything. This poster for the Midland's excursion to Newcastle races from Sheffield is typical though not the most amusing. Readers who are also railway buffs will notice that by the seventies, the Midland were a market leader and had done away with 2nd class, much to the consternation of other operators. The Midland took a modern, integrated approach to rail travel and whether it was commercial vigour, engineering expertise or style, for a time they were in the vanguard. George Stephenson did work for them, but they also understood the appeal of stylishness and how far everything from stations and publicity to refreshments could promote the railways as a pleasurable and sophisticated form of travel. From Leicester London Road to Nottingham Midland, surviving stations are confident and original and some small stations like Matlock Bath in Derbyshire and Collingham, Nottinghamshire, were remarkable if not sublime. Everyone played their part, including businesses with expertise like Bemrose.

Bemrose's son, William, became interested in applied art and wrote a book on wood-carving but the firm evidently had the ability to produce fine prints by 1840. As you see from the 1902 advertisement (second from top) colour block had become prominent in the specialist work they undertook. You will also note by then they had premises at Snow Hill in east central London. By the 1930s, they were printing off everything from colour railway posters to brochures for L.M.S. With classic overkill, Matlock was promoted not only as our own Switzerland but as a metropolis of hydropathy. (Matlock Bath station was designed to look like a chalet - wood was another feature of Midland designs).

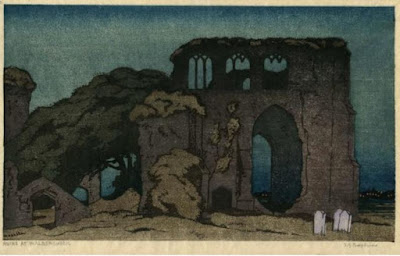

Readers will know from the previous post that Bemrose worked with Arthur Rigden Read on Valencia. But notice the similarity between the block capitals used in Hall Thorpe's Summer and S.G. Boxsius'Evening afterglow (below). I suspect this masterly woodcut from about 1936 was printed by Bemrose. Certainly if Boxsius had printed it himself, he would have signed it in pencil. (I know it isn't signed because I own it). What Boxsius, Read and Hall Thorpe all had in common is knowledge of the print trade. I cannot be sure that Bemrose printed any of Hall Thorpe's other woodcuts, but someone had to and, as you see from the standard of all the prints and posters here, Bemrose knew what they were about.